|

6.

|

Labeling

- Now that the images are in the proper order and of the desired quality, it is time to begin the labeling process. In our atlases, we have adopted the naming conventions used in The Mouse Brain In Stereotaxic Coordinates by Paxinos and Watson. A list of the abbreviations is available online.

- We must first create a text layer to contain the labels for the section. Select the text tool

and click in the approximate area of the structure that you would like to label. In the resulting window, type the abbreviation for the structure. Using the Move Tool and click in the approximate area of the structure that you would like to label. In the resulting window, type the abbreviation for the structure. Using the Move Tool  drag the label to the appropriate structure. drag the label to the appropriate structure.

- Since this is the first label, it is necessary to render the layer so that other layers may be merged on to it. In the Layer menu, select Type - Render Layer. The icon on the layer in the list of layers will change once it has been rendered.

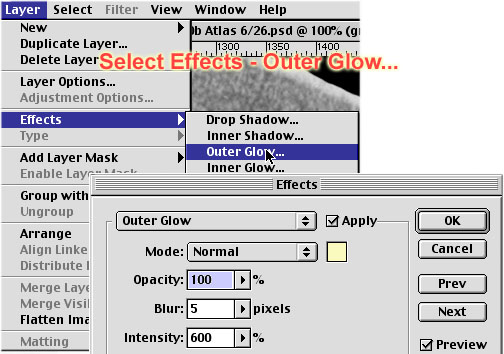

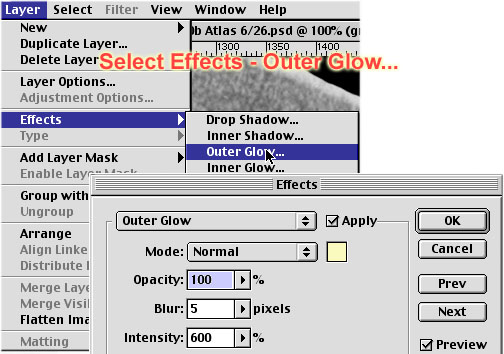

- So that the labels will standout against the background of the brain, we will apply an outer glow to everything in the text layer. Make sure that the current text layer is still selected and choose Effects - Outer Glow from the Layer menu. Select Normal Mode and experiment with the other settings until you obtain the desired result.

- We now have a text layer for this section. At this point, its name is still whatever abbreviation you typed earlier. Double click on the layer in the list of layers and give it a more descriptive name.

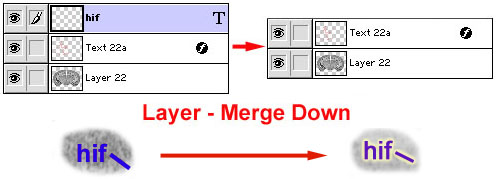

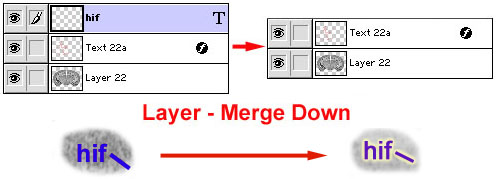

- Select the Text Tool

again and label the next structure. You will notice that this will create a new layer. Once you have placed this label in its proper position choose Merge Down from the Layers menu. This will combine this layer with the one below it (hopefully that is still the section's text layer). Since the new label is now part of the text layer it will take on the outer glow of all objects in that layer. again and label the next structure. You will notice that this will create a new layer. Once you have placed this label in its proper position choose Merge Down from the Layers menu. This will combine this layer with the one below it (hopefully that is still the section's text layer). Since the new label is now part of the text layer it will take on the outer glow of all objects in that layer.

- Sometimes drawing lines from a label to a structure adds clarity. If this is necessary, select the Line Tool

and draw the line. It too will take on the outer glow of the text layer. and draw the line. It too will take on the outer glow of the text layer.

- References: For the identification of structures in the mouse brain we refer the user to:

- The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (1997) K. Franklin, G. Paxinos, Academic Press, San Diego. ISBN Number 0-12-26607-6. (Library of Congress: QL937.F72).

- A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Albino Mouse Forebrain (1975) B. M. Slotnick, C. M. Leonard. U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Rockville, MD.

|

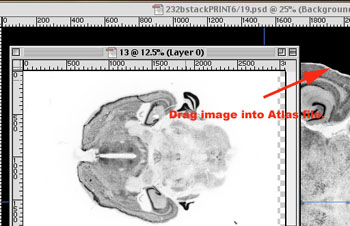

them into the already open atlas file.

them into the already open atlas file.

and draw a line down the central vertical axis of the image. Then select R otate Canvas - Arbitrary from the Images menu. The default value will come from the angle that the line makes with the perpendicular. Continue to rotate the image until you are pleased with its alignment.

and draw a line down the central vertical axis of the image. Then select R otate Canvas - Arbitrary from the Images menu. The default value will come from the angle that the line makes with the perpendicular. Continue to rotate the image until you are pleased with its alignment.

and click in the approximate area of the structure that you would like to label. In the resulting window, type the

and click in the approximate area of the structure that you would like to label. In the resulting window, type the

and draw the line. It too will take on the outer glow of the text layer.

and draw the line. It too will take on the outer glow of the text layer.